Proving the Blade: Wilkinson Sword’s Eprouvette Machine and Victorian Sword Testing

Why Wilkinson Introduced a “Proving” Machine

Victorian battlefields were unforgiving and a sword that failed at the decisive moment could mean life or death. In the early to mid-19th century, British officer swords sometimes had a reputation for ornamentation rather than strength (antique-swords.co.uk). Many young officers were carrying so-called “pipe back” style blades which tended to be very flexible and had a cross section unsuitable for cutting through thick clothing and light armor. Unlike the swords of enlisted men – which were often tested (“proved”) by the Ordnance or East India Company – officers’ swords underwent no mandatory proofing (antique-swords.co.uk). Enter Henry Wilkinson, a London swordsmith who set out to revolutionize sword making. Wilkinson’s solution combined craftsmanship with engineering rigor: a brutal new testing regimen for every blade he sold.

Here’s a Video on a brief history of the Wilkinson Company and a sword I purchased

Henry Wilkinson’s Quest for an Unbreakable Sword

In 1844, Henry Wilkinson introduced an invention that would transform sword quality: the “Eprouvette” sword-testing machine. (The term “Eprouvette” comes from French, meaning a test or proof, and had been used for devices that tested gunpowder; Wilkinson applied it to swords.) Reports from India and Afghanistan showed that too many officers’ swords were failing in combat (antique-swords.co.uk). Determined to set a new standard, Wilkinson developed this device to subject blades to forces far greater than any human could exert.

“In order to give a more severe proof than has ever been attempted, I have invented a sword Eprouvette, which will represent a power similar to, but far exceeding any human force… likened to the arm of a giant, with power sufficient to decapitate at a single stroke; after which proof, it is not likely these swords will ever break in any actual encounter.” – Henry Wilkinson (1844)

With this machine, Wilkinson could mimic the impact of the fiercest blow and ensure each blade would survive. Every sword blade Wilkinson made after 1844 was “proved” – meaning tested on this machine – before leaving the factory (fordemilitaryantiques.com). In fact, Wilkinson even invited others to bring in their own blades for testing. He advertised that on certain weekly days, officers or civilians could have their personal swords proved, and even measure the strength of their own sword-arm against the machine’s strike. It was a brilliant mix of Victorian showmanship and quality assurance: one could literally watch a machine swing with “giant” force at your sword. If the blade survived unscathed, it earned the coveted status of “Proved”.

Artist Depiction of the Wilkinson Eprouvette Machine using weights to flex a sword

Inside the Victorian Sword Proofing Process

Wilkinson’s blade-proofing process became a hallmark of quality in Victorian sword craftsmanship. After a sword blade was forged, hardened, and tempered, it underwent a rigorous testing sequence before final assembly. A contemporary company document from 1902 outlines the key steps: after heat-treatment, each blade received a strike test and a deflection (bending) test (fordemilitaryantiques.com). In practice, this meant flexing the blade to ensure it could spring back without taking a set bend, and delivering a mighty blow (via the Eprouvette machine or a drop test) to guarantee the blade wouldn’t crack or shatter. Only if the blade survived these trials was it deemed battle-worthy.

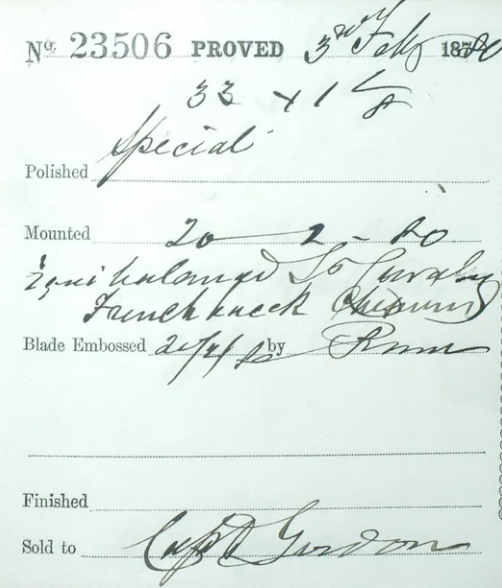

Next came the hallmark of a proved sword: the proof marking. Wilkinson’s staff would stamp the blade’s forte (the solid section near the hilt) with a special proof mark, often by insetting a small disk of brass or copper alloy into the steel. This inset disk – the famous Wilkinson proof disc – was usually engraved or embossed with symbols to indicate a successful proof. At the same time, the blade was assigned a serial number (on the spine) if it was from Wilkinson’s top-tier “best proved” range. Both the proof disk and serial number would be recorded in Wilkinson’s proof book, a ledger tracking every tested blade and its purchaser or intended recipient. In the 1850s, Henry Wilkinson himself or his manager (and later successor) John Latham personally supervised each test, literally putting their reputation behind every blade (fordemilitaryantiques.com).

Wilkinson was so confident in this process that he issued a guarantee with each sword. Officers received a printed “Proof Card” with their purchase, declaring that the sword was guaranteed and would be replaced without charge at any time if broken in fair usage. However, the card also sternly warned that no replacement would be made if the blade was broken by “bending or springing” it or by misusing it (for example, striking with the flat or performing dangerous stunts like tent-pegging). In short, Wilkinson guaranteed the sword as a weapon, not a pry-bar. The proof card even offered care tips – advising young officers not to needlessly flex their swords (to avoid weakening the steel) and to keep blades dry and oiled to prevent rust. This little document is a fascinating glimpse into Victorian quality control and user education.

A printed 19th-century Wilkinson Sword proof certificate, guaranteeing the blade against failure in fair use and giving care instructions.

An Wilkinson 1845 Pattern Officers Light Cavalry Sword

The Wilkinson Sword Proof Disc – A Mark of Quality

At the heart of Wilkinson’s branding was that small circular proof disc in the blade, which became an instant symbol of quality. Starting in 1845, Henry Wilkinson began inserting a gilt-brass disc into a countersunk hole on the blade’s ricasso (the flat section just above the hilt) for every sword that passed the Eprouvette test (fordemilitaryantiques.com). On this disc would be stamped “HW” (for Henry Wilkinson) if the blade was one of his best proved make, or sometimes other symbols if it was produced for a retail outfitter rather than directly by Wilkinson. The idea was similar to the older concept of marking blades “warranted” (used by makers in the 18th century), but Wilkinson’s proved disc was backed by a far more rigorous and standardized trial (antique-swords.co.uk). It was essentially a quality seal, visibly assuring any buyer (or opponent) that “this blade has been tested and will not fail.”

Close-up of a Victorian officer’s sword by Wilkinson, showing the small circular proof disc inset in the blade’s ricasso (base). The disc is surrounded by Wilkinson’s etched proof mark – here a six-pointed star formed by interlocking triangles. This distinctive emblem signified a blade that had passed Wilkinson’s stringent tests. (Suggested alt text: “Close-up of a Wilkinson sword’s ricasso with a gilded proof disc inset, surrounded by an etched six-pointed star proof mark design.”)

This proof mark design – often a “double triangle” starburst – was not chosen at random. According to Wilkinson Sword historian Robert Wilkinson-Latham, the triangle is the strongest shape in geometry, and two interlocking triangles were used to emphasize the strength of Wilkinson’s blades and the rigor of their testing (tapatalk.comfordemilitaryantiques.com). This Star of David-like six-pointed star became Wilkinson’s signature proof etching around the brass disk. Other makers quickly followed suit: as early as 1845–46, rival sword makers began adding their own proof slugs on officer blades (antique-swords.co.uk). They clearly felt pressured to show customers that their swords, too, were “proved” and combat-worthy. Many of these other firms adopted generic brass discs stamped with the simple word “PROVED.” In some cases, symbols like tiny fleur-de-lis or sunbursts accompanied the word. A few makers even imitated Wilkinson’s style; for instance, Birmingham makers often etched a sunburst pattern around the disc, whereas London makers (Wilkinson included) tended to stick with the six-point star motif.

As the decades went on, the proof disc evolved but never disappeared – at least not until much later. Wilkinson’s discs were usually circular, about the size of a small button, but in 1905 the company introduced a hexagonal-shaped proof disk for its absolute top-grade blades. The hexagon mark denoted a “best quality” sword, though the traditional round disc continued in use as well. Some lightweight “piquet weight” swords (dress swords for evening wear) did not get an inset disc (drilling a hole in those slim blades was risky); instead, they were just etched with a proof symbol (fordemilitaryantiques.com). By the early 20th century, for economy, Wilkinson sometimes skipped the inset brass on lower-tier swords and just etched a “W” within the double triangle directly on the blade for outfitters’ orders. The proof disc tradition endured over a century of sword-making. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1960s that Wilkinson finally phased out physical proof discs entirely, due to rising costs – afterward, all proof marks would be etched rather than inset. But for the entire Victorian era and beyond, that little glittering disc on a sword was a source of pride and reassurance.

Round Proof Discs on Wilkinson swords

A post 1905 Hexagonal Proof Disc that denotes “best quality” in Wilkinson’s proofing rankings

The Wilkinson evolution of proof discs. Note the complete removal of the disk post WWII

Legacy of Wilkinson’s Testing

Wilkinson’s Eprouvette and proofing process had a lasting impact on military sword standards and consumer confidence. In an age of industrial advances, it introduced quantifiable quality control to a product that could mean the difference between victory and defeat in personal combat. The British military eventually came to expect a certain level of proof in the swords their officers carried. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the presence of a proof disk (or etched “proved” star) on a blade was accepted as a de facto standard of a battle-worthy sword. It was not officially mandated by regulation that every officer’s sword have a Wilkinson-style proof mark, but it became an arms industry standard that reputable makers adhered to. Wilkinson’s success even encouraged the War Office to adopt stricter testing for the swords and bayonets it purchased. (For example, British bayonets in the early 1900s were routinely bend-tested – a small “X” mark would be stamped on a bayonet blade to show it had been sprung and returned to true as proof of its tempering). The philosophy was clear: a blade should not fail the soldier who wields it.

Even today, the legacy lives on in subtle ways. Many modern ceremonial swords for British and U.S. military officers still feature an etched six-pointed star with the word “PROVED” near the ricasso. This is largely a traditional homage – a nod to the rigorous testing of the past. Enthusiasts and collectors of antique swords continue to prize Wilkinson-made weapons, in part because each serial-numbered Wilkinson blade can often be traced in the company’s proof book archives for details of its testing and original owner. The proof discs and records have become a treasure trove for historians, allowing many Victorian swords to tell their stories.

Wilkinson Sword’s Eprouvette machine may now reside in storage somewhere, but its influence remains as solid as the steel it tested. The company itself shifted focus in the 20th century (famous for razors and knives today), and stopped making military swords in 2005 (fordemilitaryantiques.com). Yet, the sword-proofing tradition was picked up by others – for example, Pooley Sword, the firm that took over the UK military sword contracts, still performs rigorous blade testing (including bending and impact trials) on each sword, continuing the standard that Henry Wilkinson set so long ago (fordemilitaryantiques.com).

In the grand story of military craftsmanship, Wilkinson’s Victorian innovation stands out as a compelling chapter. It’s a story of engineers and artisans working hand-in-hand – literally forging trust in metal. The next time you see a dress sword with a tiny star or circle on its blade, remember that it’s not just a decoration: it’s the echo of a Victorian giant’s legacy, the promise that “this blade has been proved true.”

Did you find this journey into Victorian sword lore as fascinating as we do? If so, feel free to share this article with fellow history buffs or antique arms enthusiasts. Join the conversation by leaving a comment below – we’d love to hear your thoughts or personal stories about heirloom weapons and the craft of arms.

A proof Disc that may or may not be from Wilkinson. Many companies copied this marketing strategy to sell swords

Sources:

Henry Wilkinson (1844), Engines of War, excerpt on sword testing and the invention of the Eprouvettesirwilliamhope.orgsirwilliamhope.org.

Matt Easton, British 1845 Pattern “Wilkinson” Style Sword Blades – historical analysis of Wilkinson’s blade improvements and proof-testing introductionantique-swords.co.ukantique-swords.co.uk.

Robert Wilkinson-Latham, “Wilkinson’s Swords” (Forde Military Antiques, 2019) – detailed company history by Wilkinson’s descendant, describing the proving machine’s use and the proof mark variations from 1844–1960sfordemilitaryantiques.comfordemilitaryantiques.com.

Bygone Blades antique sword descriptions – examples of Wilkinson swords with proof slugs (round and hexagonal “HW”) and explanation of their significancebygoneblades.combygoneblades.com.

Journal of the Society of Arts, Vol. 21 (1873) – notes on contemporary sword proof methods (manual vs. machine)sirwilliamhope.org.